|

27/05/2021 The Withering State: Where Are Thou Sushasan Babu?

|

The public invisibility of Shri Nitish Kumar, the Chief Minister of Bihar, stands in sharp contrast to his counterparts from the neighbouring states of Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. Reportedly, Shri Adityanath Yogi has already visited seventy districts of his rather large state to review the administrative preparedness during the second wave of Corona. And, he intends to cover the remaining districts soon. Ms. Mamata Banerjee has the well-acquired reputation of being a hands-on Chief Minister. Be it cyclones like Amphanor Yaas, or the Covid-19 pandemic, people have often seen her navigating the narrow lanes and dingy streets of Kolkata with a microphone in hand effectively communicating with people on a host of issues concerning precautionary measures thereby creating awareness and generating public confidence in governmental readiness in times of calamity.

On the contrary, in Bihar, the political class, including the Chief Minister and Ministers, simply appear to have abdicated their larger responsibilities towards the public save routine bureaucratic review meetings in the state secretariat about which one comes to know through media, and the opaque authorised briefings comprising circulars, orders, notifications, memoranda and the like. Little wonder, with every passing day, we see a growing disconnect between the official claims about their concerted efforts towards effective management of Covid-19, and the monumental saga of deprivation, misery, and suffering at the ground-level. Even the villages within a radius of twenty kilometres of Patna, the state capital, present gloomy images of decaying primary health centres, and the near-absence of doctors and para-medical staff. We need not repeat the sad story of faulty and unused ventilators, the lack of ICU beds in district hospitals, and the vacant and unfilled posts of doctors and auxiliary staff in a state which fares so abysmally on all the possible indicators of human development.

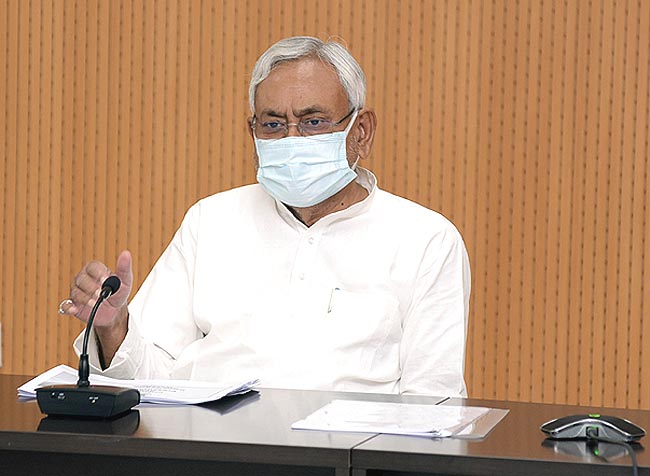

Pic: Twitter The recently circulated images of the Darbhanga Medical College and Hospital (DMCH) are proof enough of our accomplishments on the health front! If more evidence is required, one should quickly glance at the latest National Family Health Survey Report (NFHS-5; 2019-20), and do a back-of-the-envelope comparison between figures relating to Bihar and the all-India average. We appear to have become reconciled to the fact of our being a basket case lending our inglorious weight to the category of the so-called BIMARU states. In this disconsolate scenario, Nitish Kumar emerged as a ray of great optimism building on the groundswell of popular support when he became the Chief Minister of a stable government beginning in 2005. We saw the state in action: roads, bridges, regular panchayat elections, improved law and order situation, innovative initiatives in the field of primary education, and some definitive advancement in the health sector. In a state which was used to the empty rhetoric of ‘voice to the voiceless’ for the preceding fifteen years, these were refreshing changes for the better. People were enthused and eager to bury the stigma of the jungle raj. Evidently, Nitish Kumar benefitted from this lower benchmarking of popular expectations. And, in time, he was bestowed upon the sobriquet of sushasan babu. In a politically chaotic state, any semblance of rule-bound governance was a welcome departure. Of necessity, he made optimal use of the prevailing public sentiments, and turned out to be an aloof administrator heavily relying on an orthodox bureaucracy and a select coterie. For long, the intelligentsia in Bihar kept quiet allowing the Chief Minister to control media and public opinion in an unprecedented way. He was, and continues to be, the chief moulder of the entire mystique of good governance which was duly supported by the journalists and academics at large, particularly the ones associated with the Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI), Patna. This image makeover of Nitish Kumar was so complete and impregnable that even the ghastly images of the mismanagement of Nalanda Medical College and Hospital (NMCH) in the heart of Patna during the first wave of Covid-19 could not make any dent to it. Even today, the highest death rates among the doctors in Patna, their poor working conditions and paltry remunerations, have hardly reflected on his image. There are meticulously documented evidence of the all-pervasive failure of the state on the health front, but none at the top seems to be unnerved by them. For them, it is business as usual. On the contrary, the reporters and journalists are being subjected to harassment by the state for their fearless coverage of gross mismanagement of the pandemic.

In a democracy, there are likely to be charges and counter-charges of political partisanship on a range of issues of collective concern. The ruling dispensation in Bihar has invented a formulaic response to any criticisms of their governance failure. It goes something like this: are we not delivering things in a better way than what you had in the fifteen years of Lalu-Rabari’sjungle raj? This is not the most admirable pathway towards sushasan. This imperviousness to criticisms, and this refusal to learn from one’s mistakes, are the signs of an authoritarian leader. It is sad but true that Nitish Kumar is losing his administrative grasp over governance. More worryingly, he appears to have stopped enacting his role as a mass leader (which he never was). However, in the first decade of his Chief Ministership, he did make an attempt to be publicly visible. It is a matter of immense disappointment that a leader of his stature who emerged through the anti-Congress mass movement during emergency is more comfortable being ensconced in 1 Anne Marg.

It is no one’s case that a Chief Minister, or an effective administrator, should always be out rubbing shoulders with the hoi-polloi. But then, we all know in a state like Bihar where institutions of governance have frayed over the years (assuming they were robust once as most Biharis tend to believe), a visit from the top echelons of politico-administrative hierarchy has the potential to galvanise the lower rungs of administrative machinery. In a state where VIP culture is so ingrained, the visits by the Chief Minister to different districts would have surely toned up the morale of the staff at the grassroots. Even if temporarily, they would have put their act together to present an appreciable picture of their efforts to a visiting Chief Minister. More importantly, it would have signalled a message to the masses that their leader is with them in times of their distress and crisis. That would have certainly augmented their faith in the governmental mechanisms of testing, tracking, home isolation, Covid care centres, hospitals and vaccination. As of now, this public confidence in the state capacity is singularly absent. Going to a public hospital has come to mean voluntarily knocking at the door of death. Anyone who can afford is trying their best to access private health facilities. In the villages, quacks are having a field day as the villagersdepend more on them in the absence of reliable health infrastructure. Should not these gruesome images of people dying for want of care and attention move a political leader to more than everyday routine action? Should not we hang our head in shame when Bihar gets exemplified as the embodiment of everything that is wrong with our body polity? Should not our political class do an intense soul-searching when the public credibility of official data and pronouncements is at such a low? Have we left our people to their own devices and asked them to fend for themselves even in times of acute pandemic? Is our general apathy to public concerns not responsible for that debilitating sense of fatalism that we find among our people? For how long will we keep invoking our golden past of Chandragupta and Chanakya, Asoka and Buddha, Veer Kunwar Singh and JP, Vaishali and Pataliputra, Champaran and Bodh Gaya to turn a blind’s eye to the current institutional decay and governmental apathy that gets captured in this crisp expression Ram Bharose. Very simply, people are dying. They are in distress. They have lost their livelihoods with bleak futures staring at them. There is panic everywhere. Everyone is anxiety-ridden. Children are being orphaned, kith and kin are being abandoned, and communitarian resources of mutual help and support are over-stretched. Nothing is routine. Nothing is normal. Calamities galore. Should not we be asking then: where are thou, Sushasan Babu?

*Manish Thakur is Professor, Public Policy and Management Group, and the Dean (New Initiatives &External Relations) at the Indian Institute of Management Calcutta. Views are personal.

|

|