|

23/08/2014

Bihar: Psephology Trumps Ideology

|

Political ideology is the major casualty of coalitional politics that has been in the offing for quite some time now. ‘Pragmatic’ alliances do undercut ideological commitments of a political party. True, ideological purity is not a virtue in itself. But then contending ideologies contain competing visions and blueprints for socioeconomic transformation in a polity. They offer the electorate political choices. These blueprints give them a sense of the people on whose behalf the state intends to act. They tell them about the interest constellations that the state’s policies, covertly or overtly, mean to serve. They reveal to them the direction of societal change and the degree of attempted political inclusiveness of a varied citizenry. Sadly though, the academic and popular discussions of political alliances remain mired in electoral arithmetic. At their best, they talk of leadership tussles among the alliance partners.

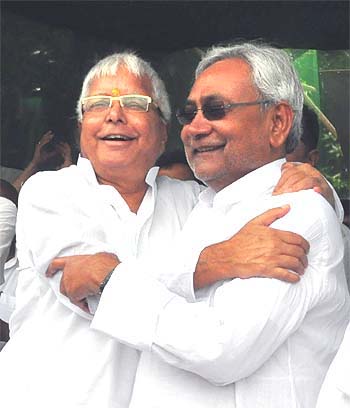

So if you scan the media reports and analyses pertaining to the Bihar mahagathbandhan (grand alliance) you will learn two things: (1) that the alliance puts together 45.8 per cent of votes under its belt as against the 39 per cent polled by the BJP in the April-May parliamentary polls and (2) the issue of future chief minister in the event of the victory of the alliance in the coming 2015 Assembly elections remains unsettled. So far as the ideology is concerned, you will come across metaphoric uses of the forces of ‘Mandal’ being ranged against the forces of ‘Kamandal’. In Lalu Yadav’s colourful language, his joining hand with his chote bhai Nitish Kumar is for the larger cause of strengthening secular forces against the communal BJP. Curiously, this grand ideological show-off hardly explains the role of the Congress, or its very presence amidst Mandal forces. Yet, this alliance recasts Ram Manohar Lohiya’s life-long politics of anti-Congressism. Interestingly, socialists of all hues swear their ideological adherence to Lohiya even as their political praxis undermines central tenets of Lohiya’s legacy. Lohiya did align with the then Bharatiya Janasangh in a parliamentary by-election in 1963, but he would not touch the Congress with a barge pole. Ironically, Lalu Yadav, a self-claimed follower of Lohiya, has been an alliance partner of the Congress for a decade now, besides serving as a Cabinet Minister in the United Progressive Alliance (I) government. In ideological terms, it is Lohiya’s anti-Congressism that paved the ground for the emergence of influential Other Backward Classes (OBCs) leaders in north India. The Chief Ministership of Lalu Yadav in 1990 in Bihar owes its glory to those political processes that made their presence felt since the late 1960s in the form of non-Congress governments in various states. Lalu Yadav then acted as the political fulcrum of lower caste empowerment that led to the total decimation of the Congress in Bihar. No tears were shed as the Congress system had come to stand for the worse forms of state-quoism in a state like Bihar. One may very well ask if Lalu is being fair to Lohiya’s legacy by lending his political shoulders to a decrepit Congress. On the contrary, Nitish Kumar’s alliance with the BJP did have historical precedents going back to the days of Lohiya. The joint struggles during the Emergency, and the Janata Party, the United Front and the NDA governments, have been the precursors to the uneasy alliance represented by the JD (U) and the BJP in Bihar. But what has been common through these alliances is their avowed anti-Congressism. Arguably, it is the anti-Congress political plank which has so often brought together a wide range of disparate political forces with their irreconcilable ideological differences. Indeed, these incompatibilities explain the short life, and the frequent breaking up, of these opportunistic alliances which are generally cobbled together under the pressures of poll performances. Psephology not only counts in these matters but also dictates terms to the alliance partners in terms of seat adjustments and the like. Undoubtedly, the Bihar mahagathbandhan is but an alliance of convenience for ensuring victory in the by-polls. It is bereft of any ideological glue of any sort. Besides embodying a distinctive ideology, a political party also represents a certain social constituency in terms of loose coalitions of castes and communities. The popular currency of psephology, as evident in journalistic and scholarly discussions, has made us believe as if the voting preferences of castes and communities remained stable and consistent over time. Thus, predictions abound about the electoral invincibility of mahagathbandhan in Bihar. The combined numerical strength of the Muslims, the OBCs, and the Mahadalits (a constituency carved out and nurtured by Nitish Kumar’s JD (U) government in Bihar) is seen as crucial for swinging the poll results in favour of the Lalu-Nitish combine. The certainty of the said victory in elections is such that infighting has already started as to who would eventually be the Chief Minister of this unsteady alliance. Such simplistic calculations overlook the ideological penetration of the BJP across caste and religious divide. The BJP in Bihar is no longer a Bhrahmin-Bania party. Its variant of nationalism has substantial pull even among the upwardly mobile sections of the OBCs and the Dalits. Its ideology of political Hinduism has a cohesive role in bringing together divergent rural caste groups in opposition to the Muslim other. Moreover, the BJP has successfully managed to project itself as the national carrier for the mobility aspirations of a large number of semi-urban and mofussil youth. In a situation where other parties are always busy with the business of making fronts and alliances, the BJP turns out to be a party with a supposedly consistent ideological focus. This ideological consistency certainly helps the BJP in bridging caste-class divide to a large extent. As the BJP has been gaining in terms of its ideological reach and the attendant communitarian polarisation, the so-called social justice parties have failed to retain even a semblance of ideological edge. The rhetoric of ‘Mandal’ and the political empowerment of lower caste groups, in fact, have led to the shrinking of the very notion of social justice. Support of caste-based quota in government jobs has become the ultimate litmus test for one’s belief in social justice. No wonder, there is not even an acknowledgement of the other possible co-ordinates of social justice. Political and policy measures towards equity-oriented growth such as land reforms, wage struggles, common education system, social sector development, public investment in agriculture hardly figure in political discourse in contemporary Bihar. Bandyopadhyay Committee report on land reforms has already been given a decent burial. And how many of us have heard of Muchkund Dube’s report on the common school system in Bihar? In a way, the narrowing down of the scope of social justice began with the advent of Karpoori Thakur in Bihar politics. In his attempt to consolidate his position amidst internecine fighting among socialists, Karpoori made caste-based reservations for the OBCs appear as the be-all and end-all of socialist politics. That also helped him project himself as the martyr to the socialist cause and the victim of high caste machinations whenever he lost control within the party in particular and political influence in general. His other policy initiatives, namely, removal of English from the compulsory list of subjects for the Matriculation examination, added up towards creating a politics of symbolism that turned its back on the socialist legacy of the 1950s and the 1960s which was suffused with grassroots struggles over substantive issues of land, irrigation, wages, employment, price control, and the like. Someone should write a political biography of Karpoori Thakur to validate the plausibility of the aforesaid. That apart, the present mahagathbandhan sounds death knell to another ideological enterprise that Nitish Kumar had initiated during his tenure as the Chief Minister. His was an attempt, howsoever feeble, to transcend the caste-based grammar of social justice to project Bihari ethnicity as an overarching identity. This Bihari ethnic identity was to be the sheet anchor for the aspirational intent to create development (vikas) and good governance (sushasan) in a caste-ridden state. His excessive reliance on the state bureaucracy did make it look like as his personal ideology than the political ideology of the party he represented. However, ethnic sub-nationalism has had the accelerating role in promoting development in other states. And, Bihari asmita did have the promise to galvanise untapped productive energy of both the resident and the émigré. Sadly, it is an aborted enterprise now as the burden of retrieving and re-activating Mandal legacy would necessitate excessive recourse to the language of forward and backward castes. It may shore up the chances of victory for the alliance in the Assembly polls next year. But it will certainly be sad for Bihar to re-discover its sushasan babu as an influential Kurmi leader, or for that matter, a junior partner playing second fiddle to the reckless Lalu in the name of Mandal politics. This new avatar of a leader of commendable qualities and modern sensibility will remain an intriguing political paradox of the twenty-first century Bihar.

| |

The recent grand alliance of the three political parties in Bihar – the Janata Dal (United), the Rashrtriya Janata Dal, and the Indian National Congress – to contest by-elections to ten seats of the state legislative assembly has somehow escaped the attention of political pundits. In the larger national euphoria generated by the promised achhe din of the Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s popular government at the Centre, the impending bad days for Bihar pale into insignificance. Even if the happenings in Bihar may be a mere knee-jerk reaction to the historic ascendancy of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) at the recently concluded parliamentary polls, it reveals much that has changed in our political culture.

The recent grand alliance of the three political parties in Bihar – the Janata Dal (United), the Rashrtriya Janata Dal, and the Indian National Congress – to contest by-elections to ten seats of the state legislative assembly has somehow escaped the attention of political pundits. In the larger national euphoria generated by the promised achhe din of the Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s popular government at the Centre, the impending bad days for Bihar pale into insignificance. Even if the happenings in Bihar may be a mere knee-jerk reaction to the historic ascendancy of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) at the recently concluded parliamentary polls, it reveals much that has changed in our political culture.