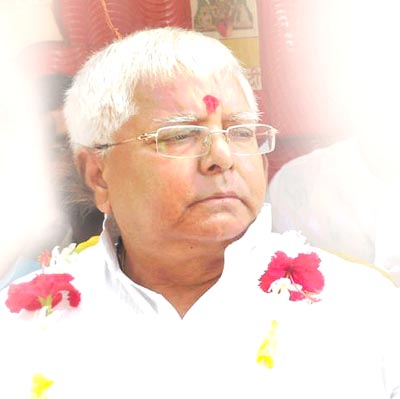

If crime and punishment were to go hand in hand, few would dare to commit a crime. Where punishment is not swift and adequate, there are likely to be more incidents of crime. The recent punishment awarded to Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) chief Lalu Prasad Yadav and former Bihar Chief Minister and Janata Dal (U) leader Jagannath Mishra and 43 others, including a JD(U) MP and four IAS officers, has created a national euphoria.

If crime and punishment were to go hand in hand, few would dare to commit a crime. Where punishment is not swift and adequate, there are likely to be more incidents of crime. The recent punishment awarded to Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) chief Lalu Prasad Yadav and former Bihar Chief Minister and Janata Dal (U) leader Jagannath Mishra and 43 others, including a JD(U) MP and four IAS officers, has created a national euphoria.

I overheard an impromptu discussion among some youths at a railway station in Kerala where the consensus was that every corrupt fellow should be sent to jail. I wondered whether our jails have enough capacity to accommodate all those who indulge in corruption, particularly when the law defines the giver and the receiver of bribe as equally guilty.

If corruption is rampant in India, it is only because we as a society are prepared to tolerate it. We do not consider ourselves corrupt when we bribe the police officer who stops our car for violating the traffic rules or engages an agent to get a driving license made. We gladly pay the police officer who visits our house to verify our passport application. We routinely try to use influence to get our work done.

A senior journalist in Thiruvananthapuram told me that he is fed up with requests for transfers, appointments with ministers and officials and jobs, all because he has a large circle of contacts in the state capital, necessary for a bureau chief. We do not consider this as corruption. At the same time, we clap thunderously when a Lalu Yadav is punished.

I have seen the rise and fall of Lalu Yadav. Once I interviewed Haryana strongman, the late Devi Lal, at the state guest house in Patna. It was still dark when the interview began. The Haryana Chief Minister was in a mood to talk, while his visitors were milling about in the lobby. The only other person in the room was Lalu Yadav, who stood throughout. When Devi Lal asked him to sit next to me, he replied, “How can I sit in front of you?” But for Devi Lal’s support, he would not have become chief minister. It is a different matter that he discarded Devi Lal like the Malayali would discard curry leaves from his sambar.

Nonetheless, Lalu Yadav was a leader in his own right. He enjoyed massive popular support. He could have done wonders to the state but he forfeited the goodwill of the people by indulging in buffoonery. He had absolutely no vision for Bihar. He could have relied on people with a vision to tap the abundant human resources of the state. The people have punished him and his party in two successive elections. He certainly merited the punishment.

I cannot say the same about his punishment by a CBI judge in Ranchi. Lalu is alleged to be involved in the fodder scam. There is no disputing that the scam occurred, though not in the proportions that the media alleged. What is the scam? Contractors were engaged by the Animal Husbandry Department to supply fodder to animals. They used to supply inflated and fictitious bills and draw money from the treasury, which would be distributed among officials and local politicians.

When a district magistrate noticed some suspicious payments from the treasury at Chaibasa in Singhbhum district, he began to investigate. Lalu Yadav was Chief Minister at that time. Cases were registered against some officials and contractors. His detractors found the scam a good stick to beat him with. The Patna High Court intervened in the case and asked the CBI to investigate the scam, alleged to be worth over Rs 900 crore. (Readers can do a Google search for my article in the Indian Express headlined “A House for Mr Biswas” which discusses how the CBI was used to hound him.)

Lalu Yadav was forced to resign and was sent to jail. A case for disproportionate assets was also lodged against him. After a long trial, he was acquitted of the charge of amassing a fortune. If he had cheated the treasury of hundreds of crores of rupees, the money should have been traced and recovered from him and his family members. Nothing of the sort has happened. Instead, he has been asked to pay a fine of Rs 25 lakh, failing which he would have to spend a few more months in jail.

Ordinarily, he should have got credit for busting the racket, which began much before Lalu Yadav arrived on Bihar’s political scene. The racket was detected and the first cases were registered when he was the Chief Minister. Far from giving him credit, his name was dragged into the scam. It does not stand to reason that the Chief Minister of a state would enter into a conspiracy with as many as 44 people to submit fake bills and draw money from the exchequer.

On a visit to Patna, over a decade ago, I asked Lalu Yadav in his house at 1, Anne Marg, about his involvement in the fodder scam. This is what he told me: “I was new to administration. As Chief Minister I could not be expected to know all the money transactions in various treasuries of the state. When a district magistrate found something fishy in Chaibasa, I encouraged him to go ahead and take action against the guilty.” Since he was an accused at that time, I do not expect my readers to believe him.

There are umpteen ways in which a corrupt Chief Minister can make money. Lalu Yadav is not such a fool that he would conspire with so many people, including his subordinate officials, to defraud the treasury. The CBI was after him for so many years but it could not unearth any ill-gotten wealth. I am sure the case would be set aside once it reaches a court of appeal. Be that as it may, his punishment has raised another issue about the eligibility of those punished to remain MPs and MLAs.

Lalu Yadav will in all likelihood lose his membership of the Lok Sabha. This follows a Supreme Court judgement in July last which said that any MP or MLA who is punished for a term of two years or more will cease to be a member of the House to which he belonged. He will also not be eligible to contest elections for a term of six years. Thus, Lalu Yadav will not be able to contest the next parliamentary elections in 2014.

How far is it justified? We often read reports that one-third or two-third of MPs and MLAs have a criminal background. Is that true? When a candidate files his nomination, he has to answer a question whether any criminal case is pending against him.

A politician has to take part in agitations. If he violates Section 144 imposed by a district magistrate to prevent any gathering of people, he invites a criminal charge. Stopping a government servant from doing his duty is yet another criminal offence. These are charges politicians routinely face. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi became Mahatma Gandhi only when the broke the law, first, at Motihari in Bihar and, later, at Dandi in Gujarat. Did that make him a criminal?

While I agree that there are criminals in politics, an overwhelming majority of MPs and MLAs in India do not have a criminal background in the strictest sense of the term. Of course, there are some who face charges like rape, murder, homicide and dacoity. Also, one should bear in mind that the law is that unless proved guilty, everybody is innocent.

Most people praise the SC verdict I mentioned. The same verdict also says that anybody who is under arrest is ineligible to contest an election on the specious plea that those who are in jail cannot exercise their franchise. If a person in power does not want a particular person to file his nomination paper, all that he has to do is to get him arrested in a trumped up case. It is surprising that the court has given such a dangerous verdict and nobody is worried about it.

Suppose a government official is convicted by a judge. He loses his job, salary and pension. If he goes in for appeal to a higher court and it acquits him of all the charges, he will get back his job, the salary he lost and other benefits. That is not the case with an MP or MLA. He will lose his position. By the time he is acquitted, another person would have been elected to the post he lost. How can it be called justice?

Congress vice-president Rahul Gandhi is impetuous. At 41, he is still a baby in politics. I do not think he studied the law his government was enacting to overcome the rigours of the SC verdict. The ordinance which the government wanted to promulgate was not all that bad.

It said that any MP or MLA punished for a term of two years or more will not lose membership of the House if he or she files an appeal. During the pendency of the appeal, the member will not get any salary. Nor will he be able to vote in the House. If he is acquitted, he will get back the salary and other perks. The ordinance had these enabling provisions but it was sacrificed at the altar of political expediency.

In the seventies when the Allahabad High Court declared Indira Gandhi’s election to the Lok Sabha invalid, Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer as vacation judge at the Supreme Court ruled that she could attend Parliament as Prime Minister but not vote as a member of the House. The ordinance in question was similar to Iyer’s verdict. Alas, it was not even discussed properly before Rahul Gandhi called it “nonsense”. The abandoning of the ordinance did not show the government in a good light.

Recently, I had a discussion with A. Sampath, CPM member of the Lok Sabha from Attingal. Until then, I did not know that he was the son of the late K. Anirudhan, a politician I respected a lot. He narrated to me an unforgettable experience of his life.

He and his parents were asleep in one room, when there was a knock at the door. His father knew who the visitor was. Immediately he got ready, gave Sampath a kiss and accompanied the visitor, who was a policeman in mufti. This was in the early sixties in the wake of the Chinese attack on India in the Northeast.

Anirudhan, who created history when he defeated former Chief Minister R. Shankar, returned home only after two and a half years. “Over all, my father spent 11 years in jail without committing any crime”. He was one of the few who remained in jail throughout the period of the Emergency.

Sampath also narrated a case in which some CPM workers were convicted in a murder case in which he was one of the defence lawyers. A Congressman while fleeing and jumping a wall, accidentally fell and died of head injuries. This incident was converted into a murder case. The lower court punished all the accused but the verdict was turned upside down by the Supreme Court.

Similarly, Father Benedict was given capital punishment in the sensational Madatharuvi murder case by the Sessions Judge but he was acquitted by the Kerala High Court. This being the situation, to make an exception in the case of politicians is contrary to all principles of natural justice. Nobody is infallible. Judges can also make blunders. The same Supreme Court had ruled during the Emergency that the citizen’s right to life stood suspended.

It is true that our political system is flawed. We need to think of ways to correct the system. We should not tar every politician with the same brush. There are good politicians as there are good officials and good citizens. We need to sift fact from fiction and uphold the principles of equity and equality. We as citizens should also have the courage to tell the Supreme Court to subject its own verdict to greater judicial scrutiny. After all, our national motto is, Satyameva Jayate (Truth alone shall triumph).

The writer can be reached at ajphilip@gmail.com

Courtesy: Indian Currents